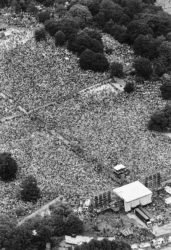

Hundreds of thousands of demonstrators gather to protest nuclear arms, on the Great Lawn of Central Park in New York, June 12, 1982. Since the election of President Donald Trump, New York City has been host to many protests hostile to his agenda, with the women’s march drawing about 400,000 participants on Jan. 21, 2017. (Keith Meyers/The New York Times)

Corey Kilgannon of the New York Times wrote about the use of the Great Lawn in Central Park for OZYFEST, “a splashy weekend long event on July 20 and 21 with multiple stages and top tickets selling for $400.” (NY Times, 7/13/19) Portions of the Great Lawn will be closed to the public for nine days in order to accommodate the festival. The use of the Great Lawn to facilitate a commercial venture raises the following questions: What and who is the Great Lawn intended to serve? The first amendment to the U.S. Constitution provides for first amendment protest rallies on the Great Lawn. Have such rallies been permitted in recent years: If not, why not?

Saralee Evans and I co-authored an article “Needed: Large Venues for Large Protest/Rallies in New York City” published in CityLand last September. In it we asserted that the Great Lawn is an iconic NYC public space that was once the venue for grand protest rallies, that for the last approximately 15 years it has been off-limits for protest rallies and that it needs to be reclaimed.

Permitting OZYFEST to utilize valuable and scarce NYC public space for its private musical, talk and food festival is an example of privatization of public space. The general premise for the use of public space should be that, it is for pubic events, free of charge. There should not be exceptions made for groups that can afford to pay large amounts of money to NYC, and who in return are given the right to close off public space.

Subsequent to the CityLand article last year, I represented the Queer Liberation march and rally celebrating the 50th anniversary of Stonewall. Negotiations over a period of seven months involved many meetings with Parks Department officials, the Central Park Conservancy and the NYPD and required the group to obtain numerous permits from city and state agencies and pay substantial fees for items such as Insurance before we obtained the permit to hold a rally on the Great Lawn on June 30. This experience leads me to believe that despite the professionalism and expertise of Alexandro Olivieri and Anthony Sama of the Parks Department and Lieutenant Kevin Lee of NYPD Manhattan North, that unless a group has lots of money, good lawyers and a top-notch organizing team, it is extremely difficult to conduct a first amendment protest rally in the Great Lawn.

The Parks Department, Central Park Conservancy, NYPD Manhattan North and civil rights lawyers and advocates need to sit down together and revisit the barriers to and rules governing the use of the Great Lawn. Currently, the process is arduous and needs to be streamlined and some of the governing rules need to be rethought.

Norman Siegel is a partner in the law firm of Siegel Teitelbaum & Evans. Norman Sigel is a former executive director of the New York Civil Liberties Union.

While I agree with Siegel’s observation that this ill-advised permitting represents a “privatization of public space. The general premise for the use of public space should be that, it is for pubic events, free of charge. There should not be exceptions made for groups that can afford to pay large amounts of money to NYC, and who in return are given the right to close off public space” my comment is that Siegel’s post ignores any sense of spatial justice in conceptualizing this administrative act as solely a concern involving the rights and exclusion of humans who protest.

Other interests are implicated such as non-protesting park habitués, the plants and animals who call the Great Lawn part of their home, and the concept of the Park itself as manicured ecosystem, all of which will be greatly disrupted if not damaged by the Ozyfest and its dense human incursion, audio pollution, dislocation and denial of access, and removal of sense of calm. Instead, it is an immoral fencing off and exclusion from the commons which extends to all life. The work of Prof. Andreas Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos of the

University of Westminster is informative here for reconceptualizing an approach to spatial justice such as exists in Central Park.

I will not address the extremely troubling coopting of public space for private profit by the neoliberal world order except to say this is wrong. It is pervasive. Americans fetishize privatization. The reducio ad absurdum extension asks what is to prevent government from taking the park in an eminent domain proceeding and building luxury condominiums under a ground lease at the next financial crisis?

I do not believe that lauding civil servants merely for performing their functions

which lead to a bad result is appropriate. Whatever the merits those mentioned the rights and interests of the many have been subjugated to the private interests on their watch.

Finaly, the need is not for functionaries to sit down with lawyers, but for a reconsideration of spatial justice and a final exclusion of private interest from public space. Sitting down with lawyers enables the current condition of privatization.