Photo Credit: NYC.gov

NOTE: This CityLaw article was previously published on CityLand on March 8, 2021 and is being reposted ahead of the NYC Primary election on June 22, 2021. For more information about the election and where to vote visit www.voting.nyc.

Registered voters in the Democratic and Republican parties will, on June 22, 2021, be asked to participate in one of the most important primary elections in New York City’s history—with an entirely new voting system. New York City’s June primary elections will be the first major test of ranked-choice voting. Rather than voting for one favored candidate to win the party nomination, voters will be asked to rank up to five candidates on the ballot in order of preference.

For voters to make an informed choice, they must understand how ranked-choice voting works, why New York City has implemented ranked-choice voting, and how it might impact who runs for public office and how campaigns are contested. Ranked-choice voting is not inherently complicated, but any change to the electoral process has the potential to confound and dispirit voters. To avoid confusion at the polls and a decline in turnout, this is the time to educate the electorate.

HISTORY OF RANKED CHOICE VOTING

New York City is not the first place to adopt ranked-choice voting. In the United States, ranked-choice voting is currently being used in such diverse places as Alaska, Maine, San Francisco, and Minneapolis. Internationally, since the early 1900s, ranked-choice voting has been used by millions of voters in Ireland to elect their president and in Australia to elect members of the national parliament.

Ranked-choice voting was implemented in each jurisdiction to improve the representativeness of the voting system and reduce negative campaigning New Yorkers, in past years, passed a variety of reforms to address these issues including runoff primaries for City-wide office beginning in 1973 and public funding of campaigns in 1988. New York City’s Charter Revision Commission of 2003 placed non-partisan elections on the ballot, but the proposal failed to get voter approval.

New York City has been considering ranked-choice voting for decades. Statewide, beginning in 2003—and in every legislative session since—bills have been introduced in the State Senate and Assembly to establish ranked-choice voting (termed instant runoff voting) in State or local elections. And, in 2010, the State Senate passed a bill to pilot ranked-choice voting in local elections, but this bill was not taken up by the Assembly. Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer introduced New York City’s first ranked-choice voting bill in 2010 when she was a member of the New York City Council, but the bill did not pass the Council. And New York City Charter Revision Commissions in 2010 and 2018 evaluated ranked-choice voting (again, termed instant runoff voting) for primary elections, but both Commissions recommended the issue for further study by future Commissions or the legislature.

Against this backdrop, the 2019 Charter Revision Commission—the first Charter Commission in the City’s history not solely appointed by the Mayor or at the direction of the State legislature—undertook a rigorous study of ranked-choice voting. The Charter Commission held over 40 hours of public testimony; received hundreds of pages of written testimony from members of the public, good government groups, and community organizations; heard from ranked-choice voting experts from across the nation and political spectrum; and worked with City and State election officials. The Commissioners, who were appointed by nine different elected officials, voted to place a ballot measure on the November 2019 ballot to implement ranked-choice voting for primary and special elections (but not general elections) for all local offices (Mayor, Comptroller, Public Advocate, Borough President, and City Council). New York City voters overwhelmingly chose to implement ranked-choice voting for these elections by an affirmative vote of 73 percent.

HOW RANKED CHOICE VOTING WORKS

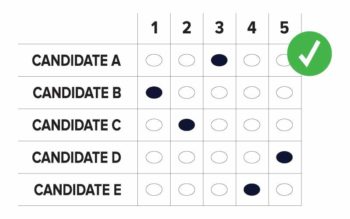

Under New York City’s ranked-choice voting system, voters will cast a single ballot and on that ballot rank up to five candidates in order of preference—first choice, second choice, third choice, fourth choice, and fifth choice—instead of voting for just one candidate. Ranking other candidates does not harm a voter’s first choice, and voters can still vote for just one candidate if they prefer.

To determine the winner of the election, all the first-choice votes for each candidate are added up. If one candidate receives more than 50 percent of the first-choice votes, they win the election outright.

But if no candidate gets more than 50 percent of the first-choice votes, then counting continues in rounds. In each round, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated and the votes for that candidate are transferred to the next-highest ranked candidate on each ballot.

So, if your first-choice candidate is eliminated because that candidate had the fewest votes, your vote is transferred to your second-choice candidate. And if your second choice is then eliminated in the next round, your vote is transferred to your third choice, and so on. In other words, in each round, your vote will count once, and it will count for the highest-ranked candidate on your ballot that is still viable and has not been eliminated, whether that’s your first choice or your fifth choice.

This round-by-round tabulation process continues until only two candidates remain. The candidate with the most votes in the final matchup wins the election.

In the City’s system, counting could have stopped once one candidate reaches 50 percent of the vote, as it would be impossible for that candidate to lose. But proceeding in the process until there are only two candidates shows whether that winning candidate has narrow majority support (e.g., 51 percent) or clear majority support (e.g., 60 percent). This final tally shows the depth of a candidate’s electoral mandate.

Let’s see how this works in practice.

Here’s an example election, with eight candidates for New York City Council and 60 total voters (including us). And here’s our ballot, where we rank the maximum 5 candidates:

We ranked Davy DMX as our first choice, so, in Round 1, our ballot counts as one vote for Davy DMX.

After Round 1, the initial tabulation of first-choice votes, here’s the results:

If this were a plurality election under the City’s prior system, José Feliciano would have won with just 27 percent of the vote.

But this is a ranked-choice election.

Since no candidate received more than 50 percent of first-choice votes in Round 1, counting proceeds to the second round, with the candidate with the fewest votes eliminated and those votes transferred to the next-highest ranked candidate on those ballots (if those ballots listed a second choice).

In Round 2, Davy DMX is eliminated, as he has the fewest total votes—2. Because we ranked Davy DMX as our first choice and he has been eliminated, our vote is transferred to the next highest-ranked candidate on our ballot—in this case, Renée Fleming, our second choice. So, in Round 2, Renée Fleming effectively becomes our top choice and our ballot counts as one vote for Renée Fleming.

Here’s what the tabulation looks like after Round 2 with Davy DMX eliminated and the two votes for Davy DMX transferred to the next highest choice on those ballots. The first of these votes—our vote—is transferred to Renée Fleming. But the other voter for Davy DMX did not rank any additional candidates, so that voter’s vote is exhausted.

This round-by-round tabulation process of elimination and transfer continues until only two candidates remain.

As shown below, in this scenario, there are seven total rounds of tabulation, with Ravi Shankar eliminated in Round 3, Patti Smith in Round 4, Paul Simon in Round 5, Yo-Yo Ma in Round 6, and Renée Fleming in Round 7—and, in each round their votes were transferred to the next highest choice on those ballots.

In Round 7 (the final round), José Feliciano and Aretha Franklin are the two candidates that remain. In the prior rounds, 12 votes have been transferred to José Feliciano from one of the six eliminated candidates, for a total of 28 votes—and 19 votes have been transferred to Aretha Franklin from the eliminated candidates, for a total of 31 votes.

So, in Round 7, Aretha Franklin wins the election, with 31 votes to 28 votes. Remember, if this was a plurality election, José Feliciano would have won with just 16 of 60 votes.

As for our ballot, in Round 7, Aretha Franklin, our third choice, was the highest-ranked candidate on our ballot that wasn’t eliminated. We had actually ranked both candidates facing off in the last round of voting. Since we ranked Aretha Franklin higher than José Feliciano, (our fifth choice), our vote counted in the last round as one for Aretha Franklin and helped Aretha Franklin win the election.

Here’s what our ballot looks like in the final round:

Importantly, when the City Board of Election releases the final certified election results, it must release the round-by-round tabulation results to ensure a complete record of results. When the City Board of Election releases the unofficial Election night tally, it has discretion to release either the total first-choice ranks for each candidate or the round-by-round results based on the ballots tabulated to date.

WHY NEW YORK CITY IMPLEMENTED RANKED CHOICE VOTING

Prior to implementation of ranked-choice voting, New York City used two election systems for primary and special elections: (1) a “plurality” system for primary elections for Borough President and City Council (non-citywide offices) and for all special elections, and (2) a hybrid plurality/runoff system for the primary elections for the three citywide offices, Mayor, Comptroller, and Public Advocate.

Under the plurality system previously used for the non-City-wide offices, the candidate with the highest number of votes won the election, regardless of the total percentage of votes obtained by that winning candidate.

The plurality system, also known as a first-past-the-post system, often results in a candidate winning with a relatively small percentage of the vote. According to a study by Common Cause New York, over the three election cycles occurring between 2009-2017, 63.6 percent of multi-candidate primaries were won with less than 50% of the vote, 29.8% of multi-candidate primaries were won with less than 40 percent of the vote, and 7.7 percent of multi-candidate primaries were won with less than 30% of the vote. For example, in the 2013 primaries for City Council—the last election with a majority of non-incumbents running—there were 23 races with three or more candidates. In those races, 16 candidates won their primary elections with less than 50 percent of the vote, and two candidates won with just 24.3 percent and 26.8 percent of the vote, respectively. With such a small winning total, it is difficult to say that these candidates represent the choice of a majority of the electorate or have clear mandate to govern.

The three citywide offices, on the other hand, used a hybrid plurality/runoff system. Under this system, if a candidate received 40 percent or more of the vote, they won. But, if no candidate received 40 percent, a runoff primary was triggered, with the top two vote getters proceeding to that runoff scheduled for a later date. This last occurred in the five-candidate 2013 Public Advocate Democratic Primary. Letitia James and Daniel Squadron were the top-two vote getters in the primary, with 36.1 percent and 33.6 percent of the vote, respectively. They proceeded to the runoff, where James topped Squadron 59.1 percent to 40.9 percent.

Runoff elections initially improved representation by preventing a candidate with less than 40 percent support among primary voters from winning the nomination. However, voter turnout for runoff elections has been consistently low, undermining the runoff election’s intended purpose.. In the 2013 Public Advocate race, there was a 61 percent drop off from the primary election to the primary runoff election. An added problem is that runoff elections are expensive. The 2013 Public Advocate runoff cost over $11 million, between election administration costs and campaign matching funds.

Ranked-choice voting addresses the problems presented by both the plurality system and the hybrid plurality/runoff system, especially in races where there are three or more candidates. In a city with an already-low turnout rate, forcing voters to come to the polls a second time for a primary runoff, and then, a third time for the general election has hurt our precarious system of representative government. With ranked-choice voting, the voters do not have to show up again at the polls for the primary runoff, so we do not risk a decline in turnout. And, by not having a primary election runoff, the City also avoids the expense of a runoff.

Most importantly for democracy, ranked-choice voting gives voters more say in who gets elected by giving them the opportunity to express more preferences on their ballot. Voters can cast a vote for another candidate that would best represent them if their first-choice candidate turns out to have little support among other voters. Even if a voter’s first-choice candidate does not win, their vote remains important in choosing the winner by ranking other candidates their second, third, fourth, and fifth choices. In this way, ranked-choice voting adds another dimension to the concept of representation.

As noted above, in the 2013 City Council races, candidates frequently won with a small percentage of the total vote. For example, in the six-way Democratic primary for Council District 24, the winning candidate, Daneek Miller, had just 24.3 percent of the vote, with the second-place candidate, Clyde Vanel, at 21.5 percent. So, 54.2 percent of the electorate voted for someone other than the top two candidates. That means over half of the electorate’s votes didn’t affect the outcome. Ranked-choice voting is especially important in these city council races. By providing voters the opportunity to express additional preferences beyond just one candidate, candidates cannot win a city council seat with such a small portion of the overall vote.

Ranked-choice voting has also led to more diverse and representative candidates running in and winning elections. Studies by Representation 2020 found that, in four California cities, San Francisco, Berkeley, Oakland, and San Leandro, ranked-choice voting did not have a negative impact on the candidacy rates for women and people of color and also increased the probability that candidates in these groups would win elections, compared to plurality elections. (Representation 2020, The Impact of Ranked Choice Voting on Representation: How Ranked Choice Voting Affects Women and People of Color Candidates in California, (Aug. 2016).)

In another study, researchers from multiple universities analyzed voting behavior in four jurisdictions—Terrebonne Parish, LA, Cincinnati, OH, Pasadena, TX, Jones County, NC—and found that ranked-choice voting “consistently” provides “slightly better” representation for minority groups. (Gerdus Benade, Ruth Buck, Moon Duchin, Dara Gold, Thomas Weighill, Ranked Choice Voting and Minority Representation (February 2, 2021).

An interesting example is the 2013 City Council race in the City of Oakland’s District 3. There, a plurality of the population, 36.8 percent, was black. That race had six candidates: one white man and five individuals of color. Counting just first-choice votes, Sean Sullivan, a white male candidate, had 26.1 percent of the vote, with Lynette Gibson-McElhaney, a woman of color, coming in second with 23.7 percent of the vote. If it had been a plurality election, Sean Sullivan would have won. But, because Oakland used ranked-choice voting, Gibson-McElhaney won the election in the final round of tabulation.

Ranked-choice voting can also change the dynamic of a campaign and leads to more civility and less negative campaigning. Candidates are encouraged to build broader coalitions of voters during the campaign because candidates who are not your top choice still will likely need your support to win.

Academic researchers conducted voter surveys in three ranked-choice voting jurisdictions in 2013—Minneapolis, MN; St. Paul, MN; and Cambridge, MA. They found that these voters perceived fewer negative campaigns than voters in plurality jurisdictions, and they hypothesized that this was because, under ranked-choice voting, candidates are encouraged to build broader coalitions of voters and align with opponents who share their same views in order to garner second and third choice votes. (Todd Donovan, Caroline Tolbert, and Kellen Gracey, Campaign Civility Under Preferential and Plurality Voting, 42 Electoral Stud. 157, 157-63 (2016); Caroline Tolbert, Experiments in Election Reform: Voter Perceptions of Campaigns Under Preferential and Plurality Voting, (Prepared for presentation at the conference on Electoral Systems Reform, Stanford University, Mar. 15-16, 2014).)

In city-wide elections with multiple candidates, it will be difficult for a candidate to hit the 50 percent threshold in the first round of voting. With ranked-choice voting, even if a candidate comes in first in the first round, they are not guaranteed to win once all the votes are tabulated. Candidates can actually be in second or third place in the first round of voting, but can still win the election in the final round by attracting more second or third choice votes. A winning campaign will recognize the perils of negative campaigning in an election where the margin of victory could very well depend upon a voter’s second or third choice candidate preference.

City government, including the Campaign Finance Board, the NYC Civic Engagement Commission, and the City Board of Elections, must conduct robust education campaigns, with community organizations and good government groups, to ensure that voters know how to fill out their ballots correctly and how the tabulation system works. Fortunately, that work has already started and will continue through June. The New York City Campaign Finance Board and NYC Civic Engagement Commission, the NYC Board of Elections, WhosOnTheBallot.org and Ranked Choice NY provide opportunities for you to learn more about ranked-choice voting. Resources include webinars, information, resources, and speakers to assist organizations willing to sponsor a ranked-choice voting educational event. You can also volunteer to be a ranked-choice voting educator. FairVote provides you an opportunity to practice ranked-choice voting by creating your own ranked-choice voting poll.

We expect that ranked-choice voting in New York City will help ensure that candidates are more representative of the diverse communities in our city; encourage coalition formation during campaigns; create the condition for a more civil and less negative election discourse; increase voter turnout and ultimately give us all a greater voice in our democracy.

Ester R. Fuchs is a Professor of International and Public Affairs and Political Science at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs, the director the Urban and Social Policy Program, and the director of WhosOnTheBallot.org.

Nicholas P. Stabile is Chair of the Board of Ranked Choice NY and as advisor to Rank the Vote. He served as Counsel to the New York City 2019 Charter Revision Commission, where, with his colleagues, he designed and drafted the City’s ranked-choice voting law.

This is a very clear, full explanation of ranked-choice voting. And the example using musicians shows RCV is not rocket science. If you’re not into musicians, imagine ranking your preferences in ice cream cone flavors. (Hey, your favorite flavor might not be available, so being able to navigate the complexities of choosing a second, or even a third, choice flavor might be critical if you don’t want to pass on having a cone.)