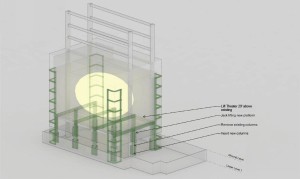

Architect rendering of the proposed Palace Theater changes. Image credit: PBDW Architects

Renovations will allow for better utilization of space, according to applicants, while preservationists expressed concerns about fragility of early-20th-century Baroque theater. On November 24, 2015, Landmarks approved an application to raise the Palace Theater, an interior landmark, 29 feet within its current footprint, as well as conduct restoration work and other associated renovations. The original building in which the theater stood was demolished, and a new hotel built over and around the theater in the 1990s. The 1913 Beaux-Arts landmark, located at 1562 Broadway, is currently being operated as the Helen Hayes Theater.

Maefield Development’s Paul Boardman stated that the firm was implementing the project in cooperation with the theater’s owners, the Nederlander Organization, and said that the theater deserved to be “nurtured, cherished, invested in, and improved.” Nederlander’s Nick Scandalios called the theater a “very special jewel,” that needed lobby and amenity space to match its grandeur. Scandalios said the proposed work would enhance the theater-going experience, and allow the auditorium to operate and remain meaningful to the City and audiences for the next century.

Scott Duenow, from PBDW Architects, detailed the other work involved in the project, which included the creation of additional back-of-house space, lobby space, and bathroom facilities, as well as new orchestra level. Duenow conceded that the idea of moving a landmarked interior “sounds a little scary at first,” but said that the project would ultimately serve to provide the theater with the “dignity it deserves.” The Palace is unusual among City theaters for having its main entrance on Broadway. Duenow proposed a plan that would provide the theater with a new dedicated entrance on 43rd Street, with a new marquee and renovated facade. The painting and decoration of the theater would be restored, and a chandelier would be installed where one once hung before the room’s conversion to a movie theater. A new escalator and set of stairs would be installed to enable patrons to reach the lobby, as well an elevator for handicapped accessibility. The back wall of the theater at one of the balcony levels would be moved eight feet to accommodate a stairwell for public-circulation purposes.

Duenow found precedent for the moving of historic structures in the relocation of Hamilton Grange in 2008 and the Empire Theater in 1998.

Higgins & Quasebarth consultant Elise Quasebarth explained that the theater was originally built as a vaudeville house, and lacked many of the amenities found in many of the City’s other theaters. She said the work was appropriate from a preservation standpoint because the landmarked interior was completely divorced from its historical physical context due to the demolition of the original building that had surrounded the theater and the construction of the new hotel above and around the landmark. She also said the proposal merited approval dueto the associated restoration plan, and the technological sophistication of the engineering that would be involved.

Engineer Anthony Mazzo, of Urban Foundation Engineering, described the process by which he planned to raise the theater. The raising would be done “one inch at a time” by a telescopic hydraulic column system, propelling the theater from below with uniform pressure while the theater was guided by a rail system at each corner, over a span of weeks. The firm has undertaken extensive surveying of the theater, and Mazzo said the elevation process would be intensely monitored. Mazzo said of the process, that once the theater is raised one inch, “the rest is just repetitive.” He stated that the intention was to move the theater “so slowly it doesn’t know it’s moving.” Mazzo said that theaters were generally built as rigid cubes, well “stabilized in space.” That would maintain its structural integrity through the elevation. After being elevated the theater would be fixed in place by mini caissons while new columns and trusses are inserted.

Mazzo was the lead engineer on the successful lateral relocation of the Empire Theater in 1998, which he said was a more difficult job than the Palace Theater proposal, which was accomplished without damaging the building’s fabric, or even disturbing pigeons on the roof. Mazzo asserted that there was no danger to the plaster ornament of the Palace Theater, and that the engineering was “overdesigned” to make for multiple redundancies that would prevent accidents, like the failure of one individual jack, from negatively affecting the process. Duenow stated that that preservation consultant Judith Saltzman would serve as an advisor throughout the process.

New York Landmarks Conservancy Technical Services Director Alex Herrera did not object to the plan in theory, given that the theater had already been removed from its original context, and commended the proposed restoration work. Herrera expressed concern, however, that the project’s success relied on “so many moving parts.” Preservation architect Dan Allen, of CTA Architects, cautioned that “theaters are fragile,” and largely composed of chips, plaster, jute, and burlap. Tara Kelly, representative of the Municipal Art Society, worried about the precedent that would be set if Landmarks approved the project. The Historic Districts Council’s Kelly Carrol alleged that the applicants were endangering the historic theater to create ground-floor retail space, in what she called “a blatant land grab.”

Chair Meenakshi Srinivasan stated that the Commission had received communications in support of the proposal from Manhattan Community Board 5, the Times Square Alliance, and the Building and Construction Trades Council of Greater New York. Paul Boardman added that the Theatrical Stage Employees union was also in “emphatic” support of the proposal.

Commissioner Michael Goldblum inquired as to whether Landmarks could mandate that the proposal be subject to a peer review at the applicants’ expense. Landmarks Counsel Mark Silberman advised that the commission could make it a condition of approval that the applicants retain an engineer that would monitor the project and report directly to Landmarks staff, or, alternately, request that engineers from the Department of Buildings review and monitor the work.

Srinivasan called the proposal a “great project” conceptually, which would aid in perpetuating the landmark’s intended use, in itself a worthy preservation goal, in addition to the value of the planned restoration. She further added that the preciousness of the interior’s fabric meant that the applicant and Landmarks would need to work together to ensure that the repositioning was successful. The Chair rejected any concerns about the project setting a precedent for other landmarks, finding that the theater had a “history of being an anomaly.”

Commissioner Fred Bland supported the project, finding that “the reward is worth the risk,” because of the contribution the project would make to the “long-term viability” of the theater. Commissioner Michael Goldblum opined that, as stewards of the landmark, the commission needed to craft a mechanism for peer review and monitoring. Goldblum noted that plaster is very fragile, and “once it’s broke, it’s broke.” Commissioner John Gustafsson said that he was willing to take the risk of approving the proposal, but added that “it’s not just their necks that are on the line, but ours as well,” should the interior be damaged.

The commissioners unanimously voted to approve the project, after imposing several conditions upon the project’s procession. Before a certificate of appropriateness is issued, the applicants must provide an independent peer review of the process that is satisfactory to Landmarks staff. Should the peer review raise any concerns, the proposal must return to the commission. Independent review will continue throughout the process of raising the structure.

LPC: Palace Theater, 1562 Broadway, Manhattan (17-7951) (Nov. 24, 2015) (Architect: PBDW Architects).

By: Jesse Denno (Jesse is a full-time staff writer at the Center for NYC Law)