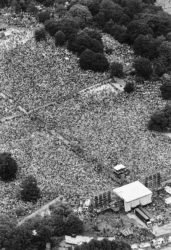

Image credit: Jeff Hopkins.

Peaceful protests, protected by the First Amendment, are fundamental to our constitutional system and to democracy. Peaceful protest marches and rallies have been instrumental in bringing about significant change in racial, gender, LGBTQ and economic equality; reproductive rights; climate policy; capital punishment; housing; criminal justice, and voting rights. Yet in recent years appropriate venues have been unavailable for large peaceful protests, raising the question of whether City practices inappropriately limit the exercise of First Amendment rights. The City needs to review its policies regarding the use of Central Park’s Great Lawn and Times Square for large First Amendment protest marches/rallies. If the City does not re-assess the appropriateness of the Great Lawn and Times Square the issue should be litigated.

Right to Peaceful Protest

The right under the First Amendment to protest peacefully is well-established. In a seminal 1939 First Amendment case, Hague v. Committee For Industrial Organization, 307 U.S. 496 (1939), the Committee for Industrial Organization sued Frank Hague, then Mayor of Jersey City, and others. The CIO alleged that Hague violated the CIO’s rights of free speech and assembly by denying them “the right to hold lawful meetings in Jersey City on the ground that they [were] Communists or Communist organizations,” and that Hague had prohibited and interfered with the CIO’s distribution of leaflets and pamphlets.

Justice Owen J. Roberts issued a concurring opinion in the CIO’s favor, writing:

Wherever the title of streets and parks may rest, they have immemorially been held in trust for the use of the public and, time out of mind, have been used for purposes of assembly, communicating thoughts between citizens, and discussing public questions. Such use of the streets and public places has, from ancient times, been a part of the privileges, immunities, rights, and liberties of citizens. The privilege of a citizen of the United States to use the streets and parks for communication of views on national questions may be regulated in the interest of all; it is not absolute, but relative, and must be exercised in subordination to the general comfort and convenience, and in consonance with peace and good order; but it must not, in the guise of regulation, be abridged or denied.

In another concurring opinion, Justice Harlan F. Stone added:

It has been explicitly and repeatedly affirmed by this Court, without a dissenting voice, that freedom of speech and of assembly for any lawful purpose are rights of personal liberty secured to all persons, without regard to citizenship, by the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Much more recently, a federal district court in Colorado underscored the principle of protecting peaceful protest in the 2008 case of American Civil Liberties Union of Colorado v. City and County of Denver, 599 F.Supp.2d 1141 (D. Colo. 2008). Civil liberties organizations and protest groups sued the City and County of Denver, the United States Secret Service and others, alleging that the security plans put in place for the 2004 Democratic National Convention violated freedom of speech and of assembly under the First Amendment.

Although Federal District Court Judge Marcia Krieger upheld the security restrictions, she pointed out that:

“Traditional public fora”— namely, public streets, sidewalks, and parks—have long been recognized as places in which assembly, communication of thoughts between citizens, and discussion of public issues should be welcomed. Such places “occupy a special position in terms of First Amendment protection,” and the government’s ability to restrict expressive activity in such public fora is “very limited.”

Recent NYC Protests

On June 30, 2018 thirty thousand New Yorkers attempted to exercise their First Amendment rights by peacefully protesting the federal government’s zero tolerance policy towards undocumented immigrants and the practice of separating families at the Southern border. The protesters planned to gather in Foley Square near the Manhattan end of the Brooklyn Bridge, march over the Brooklyn Bridge, and rally at Cadman Plaza in Brooklyn. The initial gathering was so large that it overflowed from Foley Square to the adjacent park and streets and onto the steps of the New York State Supreme Court building. When the protesters approached the Brooklyn Bridge, the walkway proved so narrow that demonstrators, according to The New York Times, “inched across the Brooklyn Bridge . . . for more than two hours.” Many demonstrators were discouraged from making the journey and others arrived at Cadman Plaza after the rally ended.

Hundreds of thousands of demonstrators gather to protest nuclear arms, on the Great Lawn of Central Park in New York, June 12, 1982. Since the election of President Donald Trump, New York City has been host to many protests hostile to his agenda, with the women’s march drawing about 400,000 participants on Jan. 21, 2017. (Keith Meyers/The New York Times)

This was not the first time that protestors’ ability to participate meaningfully in a demonstration in New York City was thwarted. When we participated in the first Women’s March in New York on January 21, 2017, we gathered on Second Avenue and, with thousands of other New Yorkers, were forced to stand in place for one and one half to two hours. Some, in frustration, left and did not participate in the march.

Shortly after the first Women’s March, Gina Bellafante, a columnist for The New York Times, questioned whether New York City today has the capacity to hold large First Amendment protest rallies. She wrote in a January 27, 2017 article that there were an “astonishing 400,000 participants” at the January 2017 Women’s March, and further described the scene:

The point of departure was Dag Hammarskjold Plaza, a small stretch of land between First and Second Avenues in the 40s, which has been a popular site of mass demonstration for many years, and one for which the city has often granted permits. It is a spot both hard to access via public transportation and relatively small, with a capacity of only 8,000 people.

The surrounding side streets are narrow and heavily shaded. The planned route for the march, south toward 42nd Street and then west toward Fifth Avenue, was difficult to approach because so many were trapped inside the plaza. Some got panicky; some pushed and shoved. Some never made it to the actual march at all.

Bellafante contrasted the Women’s March with previous protests in Central Park:

Throughout the years of social unrest in the 1960s and ‘70s, the Great Lawn in Central Park was a common ground of collective discontent. Dispersal from the park was easy; the crowds spilled out onto Fifth Avenue. In June 1982, the lawn provided the space for one of the biggest political protests in American history, as hundreds of thousands gathered to peacefully oppose nuclear arms. Delegations came from Vermont and Zambia. But two years earlier, the Central Park Conservancy had formed to save the park from the ratty state in which the city’s fiscal crisis had left it. As the park was transformed, it became less responsive to political expression.

On Saturday, January 20, 2018 we attended the second Women’s March which reportedly attracted more than 200,000 protestors. We joined the march on 72nd Street and Central Park West and were unable to progress. We stood still between 71st and 72nd Streets for approximately 90 minutes. The street was packed with people peacefully protesting in support of women’s rights. We could not see or hear the rally speakers. Our group then decided to leave the street and to walk on the east side of Central Park West. We were able to reach 66th Street, but could not proceed farther south. We left the protest and walked into Central Park. We saw other groups, families and individuals, with protest signs, buttons, and hats also leaving Central Park West and entering the park.

On March 24, 2018 the “March for Our Lives” gun control rally/march in New York City drew nearly 200,000 protestors. The formation and the rally were on Central Park West beginning at 59th Street and going north. The New York City Police Department separated the participants block by block, using metal barriers to pen in the peaceful participants reminiscent of the security strategy employed in Times Square during New Year’s Eve. This approach divided the participants and diminished the feeling of unity as well as the important visual effect of the protest.

Unconstitutional Restraints

Overly broad restraints on marches and protests violate the constitution as was held in Amnesty International, USA v. Battle. 559 F. 3d 1170 (11th Cir. 2009). Amnesty International alleged First Amendment violations during a protest rally in Miami, Florida planned to occur near the Torch of Friendship in downtown Miami. The police commanders created “a police cordon 50 to 75 yards” from the protest area and prohibited anyone from entering the area. The protestors could not hear or see the speakers because the police cordon kept them at too great a distance. Amnesty International argued that the police actions rendered the protest ineffective because no one could attend, see or hear the demonstration.

The 11th Circuit held that Amnesty International’s First Amendment rights were violated. The court, stated in part:

Amnesty also has a constitutional right to engage in peaceful protest on public land, such as in a city park. . . .Governments may not prevent protests, punish the exercise of the right to protest peacefully by arresting the demonstrators ….

The Eleventh Circuit relied on the U.S. Supreme Court decision of Saia v. People of the State of New York, 334 U.S. 558 (1948), which it cited for the principle “that the First Amendment carried with it a ‘right to be heard’. . . .”

Large Venues in New York City

It is time to reconsider using the Great Lawn in Central Park and Times Square for large peaceful protests/rallies or to find appropriate alternative sites. The fact that many thousands of New York demonstrators could not hear or see the speakers at the January 20, 2018 second Women’s March rally made the rally less effective for the organizers and less meaningful for the demonstrators.

We have observed from television reports, news accounts, and comments by participants that marches and rallies in other cities appeared to take place in a large central venue (e.g., a park) where speakers could be seen and heard. Additionally, police did not set up metal barriers penning in the peaceful participants to separate the participants block by block.

Not so long ago large First Amendment protests were held on the Great Lawn in Central Park and in Times Square. Perhaps the single largest New York City protest occurred on June 12, 1982 to protest nuclear weapons. The size of the demonstration was variously estimated to be 550,000 to 600,000 to as much as 700,000 to 1.2 million people. The protesters marched from the United Nations to the Great Lawn and surrounding areas in Central Park where a rally occurred with speakers, including Coretta Scott King and entertainers Bruce Springsteen and Joan Baez.

The City has since severely limited the availability of Central Park and Times Square for demonstrations. In 2004 the National Council of Arab Americans and another organization sued the City for denying their request for a permit to hold a rally of 75,000 people on the Great lawn of Central Park, two days prior to the 2004 Republican National Convention at Madison Square Garden. U. S. District Court Judge William Pauley denied the plaintiffs’ motion for a preliminary injunction.

In denying the injunction Judge Pauley ruled that “a municipality’s goal of managing and maintaining park facilities constitutes a significant government interest.” Judge Pauley further found that the Parks Department’s reasons for denying the permit were content neutral. Nat’l Council of Arab Americans v. City of New York, 331 F. Supp. 2d 258 (S.D.N.Y. 2004) Judge Pauley observed that the protest organizers had not met the requirements of providing a rain date or a plan to ensure that the number of the demonstrators would not exceed 80,000, the number Parks estimated could be accommodated on the Great Lawn. Judge Pauley also found that Parks had “satisfactorily made alternative channels of communication available,” such as the East Meadow of Central Park, which could hold 50,000, people, as well as other park sites in the Bronx and Queens.

The lawsuit was ultimately settled in January 2008. Under the settlement the Parks Department agreed “to undertake a feasibility study to obtain a recommendation as to the optimum and sustainable use of the Great Lawn for large events including rallies, demonstrations and cultural events.” The completed report was concluded on July 16, 2009 that (1) there should be an upper limit of 55,000 persons at large events held at the Great Lawn, if the Turtle Pond area is included; (2) the Parks Department and/or the Central Park Conservancy should have the ability to cancel large events due to inclement weather; and (3) in addition to the six events that were already allowed during summer months, one more large event could be scheduled during the fall or spring, but not both. The Great Lawn Study Committee, A Report on the Great Lawn, Its Public Use, Maintenance, and Repair, 10 (July 16, 2009).

Current regulations largely follow the recommendations of the feasibility study, inter alia, capping large events at 60,000 persons; allowing for seven large events per year; and allowing the Parks Department Commissioner to cancel events based on factors including extreme weather, rainfall, soil saturation, and other field conditions that could cause significant damage to the Great Lawn or surrounding areas. New York City, N.Y., Rules, Tit. 56, § 2-08(t).

In these controversial times, when protests have attracted hundreds of thousands of participants, there is renewed interest in and need for sites for large First Amendment rallies. The City should re-evaluate the policy of limiting the use of the Great Lawn to only seven large events per year (four of which are allotted for performances by the Metropolitan Opera and the New York Philharmonic) and capping the capacity at 60,000 people.

The Great Lawn is one of the few venues in the City that can accommodate such rallies. While we understand the importance of protecting the Great Lawn, serious consideration should be given to making the Great Lawn more available. We suggest that the City Council hold public hearings on the subject of whether New York City currently provides an adequate venue for large First Amendment marches/rallies. Some of the questions that need to be answered are:

- Should the 2009 study, which did not adequately address First Amendment concerns, be the definitive statement on the use of the Great Lawn and its periphery areas for large First Amendment rallies?

- How many large events have occurred on the Great Lawn since the 2009 study? How many were allocated to concerts, such as those by the Metropolitan Opera and the New York Philharmonic? How many were allocated for events that concern free speech?

- Is it correct for the Parks Department to limit the capacity of the Great Lawn and the surrounding areas to 60,000? The pictures from the past (e.g. 1982 Anti-Nuclear Rally) show hundreds of thousands of protestors were not only on the Great Lawn but were scattered throughout the periphery of the Great Lawn.

Lastly, Times Square should also be re-opened for political protest rallies. New Year’s Eve crowds in and around Times Square swell to 2 million people.

Conclusion

New York City can no longer ignore the dilution of First Amendment Rights that results from the inadequacy of current venues for demonstrations and rallies. The City needs to review its policy positions regarding the use of Central Park’s Great Lawn and Times Square for large First Amendment protest marches/rallies.

Norman Siegel and Saralee Evans are partners in the law firm of Siegel Teitelbaum & Evans. Norman Sigel is a former executive director of the New York Civil Liberties Union. Saralee Evans is a retired New York State Supreme Court Judge.

The article suffers from an anthropocentric bias.

Maintaining any parkland, even a manicured lawn, is significantly more important than any claimed need to accommodate the human angst or cause de jour. Street protests are literally where they should be and this lessens environmental harms. It also serves to highlight the adversarial nature of what protest means which is a confrontation of ideas. With protests on the great lawn, the protestors end up merely congratulating each other instead of facing off against the cause of their protest. For example, protests against British Petroleum or the Japanese government should rightfully be held at the offices of the subject of the protest, not in a park. In fact, seven event for 60K humans pursuant to New York City, N.Y., Rules, Tit. 56, § 2-08(t) is probably too many and the Parks dept. should reduce the size of public events to no more than 20K.

The Central Park Conservancy is being a bit precious regarding the use of the great lawn. It is, after all, only turf. Protest is more essential now than ever. The first anti-Trump rally after the election was held on CPW north of Trump Plaza.

Police crowd control similarly restricted access, making it near impossible to join the protest (ie no use of side streets) or hear the speakers. It seemed that was merely to protect the delicate sensibilities of super-wealthy in adjacent towers.

Frankly, a large demonstration should be one of the perks of living in NYC. As we privatize ever-more spaces, by off-sourcing their care to groups with no accountability to the public, our freedom is ever-more constrained. One can be sure that the big plaza at Hudson Yards’ll also be off-limits.

I remember Rudy Giuliani closing down City Hall Park for much of his mayoralty. Supposedly for improvements, but oddly none at the steps, which had long been the spot for protests. Showing his autocratic streak 35 years ago, he made sure to silence the voice of the people. Democracy is more important than lawn!